Aspects of this issue have been dealt with before in this magazine – see Winn, “Can Rent-to- Own Payments Affect Credit Scores?” RTOHQ: The Magazine, July-August 2012, pp. 28-32. This time around, we will look at changes in the RTO marketplace and in the Consumer Reporting Agency (CRA) world as well.

It has long been a marketing mainstay of RTO to advertise “No Credit Check” or something similar — “No Credit Needed” or “No Credit Required.” Depending upon whose survey one reads, that message is aimed at anywhere from 20% to nearly 50% of the U.S. population. Those are the people who are “credit-challenged,” who have “blemished credit,” or who, in the lingo of the credit reporting agencies, are “thin file” or “no file” consumers. The former are all those people who have applied for credit somewhere along the way to buy something – be it large such as a house, or something smaller like a microwave – and been turned down, because their credit score, based on their bill-paying and other habits, was deemed too low by the prospective creditor. The latter are consumers with no credit score, because they are too new to the marketplace to have accumulated sufficient information about themselves for the CRAs to be able to give them a score.

Not running credit has never meant that RTO dealers are renting stuff blindly to anyone and everyone, even though in some stores, it may sometimes seem that way.

The message from the rent-to-own industry to these consumers is that if the system won’t allow you to borrow enough money to get what you want or need, you can get it from us, because we don’t care if you happen to have no credit. The RTO industry wants to rent you what you want anyway, and you can get it today.

The reason that credit reports and credit scores loom so large in the U.S. economy is that consumer credit is an important engine driving growth in the country, and because those tools are used to assess risk in getting repaid. The underlying assumption is that past behavior is likely to be indicative of future behavior. If someone, historically, has not been good at paying bills on-time, that is evidence of some likelihood that such behavior will continue. It is, of course, more complicated than that. People may have trouble paying bills because they are financially irresponsible, or perhaps merely scofflaws intent on scamming the system. More often, though, people fall behind on their bills because they have more outgo than income, either chronically because they lack self-control and overspend or, as is more often the case, emergencies arise that pull cash from the bill-paying pile.

RTO dealers historically have not bothered running credit on customers because they simply did not care what a customer’s FICO score was. If the customer was honest on the rental application, all things being equal, he could rent a TV, and if the customer’s past history of not paying bills on-time washed over into the rent-to-own transaction, no matter. The store was, of course, hoping that the customer would make timely renewal payments and ultimately get to own the TV and, indeed, come back to rent more stuff later. But if he didn’t manage to do that for whatever reason, no harm done. The customer could simply give the TV back to the store – no harm, no foul.

Dealers do want to know to whom they are renting. They will verify identity, home address, employment where and for how long, and other details that vary by dealer, most often gleaned from the customers themselves and then verified with calls to landlords, employers, and personal references.

At the front end of the relationship between the customer and the dealer, there is nothing preventing dealers from getting a credit report if they want to, and the world of credit reporting has changed dramatically over the years. Once, there were just the big three credit reporting agencies: Experian, Equifax, and Transunion. Today, there are many, many more CRAs than just the big three. The National Consumer Law Center’s publication, Fair Credit Reporting, Vol. 2, Appendix (2017) has a list of 98 CRAs with names, addresses, telephone numbers, and websites. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which now has regulatory jurisdiction over CRAs, publishes a list with alternate CRAs with descriptions of the kinds of information they collect on consumers: https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-reporting-companies-list_2021-06.pdf.

While brick-and-mortar rent-to-own dealers have largely been indifferent to credit checks, the virtual RTOs almost have to run some kind of credit check on their wouldbe customers. They’re dealing with consumers at more than arms’ length, perhaps through the company’s website and via the consumer’s email. There is no personal encounter, and the consumer might live several states away. It is the prevalence of virtual RTO and the proliferation of alternate CRAs that makes the issue of running credit on would-be rent-to-own customers relevant.

Can RTO dealers run credit on applicants, even though they will not be extending credit in the transaction? Yes. Absolutely. Who can run credit and for what purposes is controlled by the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (15 U.S.C. secs.1681 et seq.), and perhaps to some extent, by the federal Equal Credit Opportunity Act (42 U.S.C. secs. 1691) and Regulation B (12 C.F.R. secs 1002 et seq.). Not just anybody can run credit on a person for any reason. There are four permissible reasons listed in the FCRA: credit, employment, insurance, and “legitimate business need.” Rent-to-own dealer inquiries fall into this fourth category, as those inquiries are “in connection with a business transaction initiated by the consumer.”

Dealers wanting or needing to run credit on a consumer can get two different kinds of information. The first is a credit report, the history of the consumer’s bill-paying and other habits over time. The FCRA defines a credit report as information that bears on the person’s “creditworthiness, credit standing or capacity, character, reputation, personal characteristics, or mode of living.” The second kind of information is a credit score, often a FICO score that puts a number on the consumer’s creditworthiness between 300 and 850. How a credit score is derived from the consumer’s credit history is a closely guarded trade secret and was outlined in the 2012 article referenced above. A consumer credit score is not static and changes over time as one moves through life. Merchants, including RTO dealers, can get one or both kinds of information.

It should be apparent to all that if a dealer runs credit and gets any of this kind of information from a CRA, the dealer cannot advertise “No Credit Check” or anything similar that would give the impression that there will not be some inquiry. That would be deceptive.

In addition, two states, Arizona and California, have language in their rent-to-own statutes that restrict dealers’ ability to report customer payment histories to CRAs. Dealers cannot do so in these states unless they have pulled credit on the consumer upfront, or if they advertise “No Credit Check” or something similar.

It is the prevalence of virtual RTO and the proliferation of alternate CRAs that makes the issue of running credit on would-be rent-to-own customers relevant.

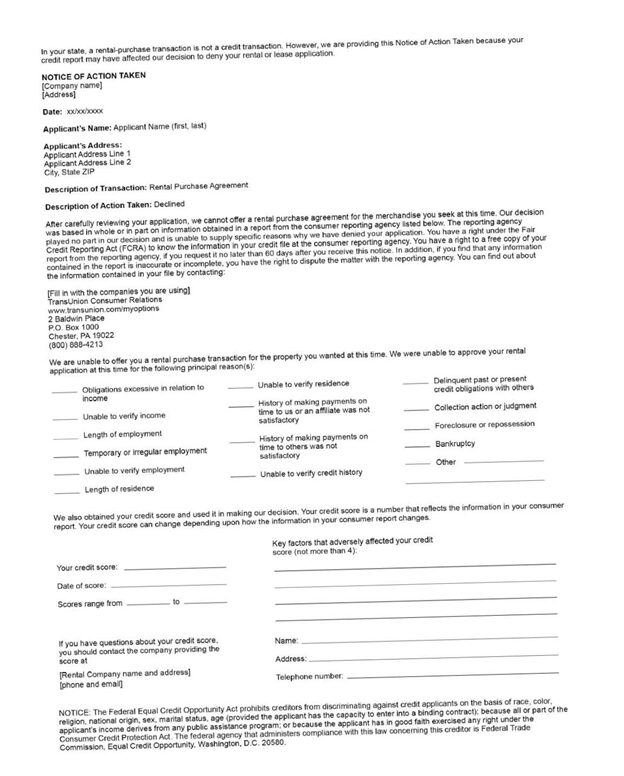

Dealers who choose to get a credit report or a credit score on a consumer have a few rules to follow. Most importantly, if the dealer uses the information in whole or in part to turn down a would-be customer, or alternatively, change the terms of any deal initially proposed, certain safeguards kick in. The dealer must send the consumer a “Notice of Adverse Action.” That notice, at the very least, must contain contact information for the CRA, so that the consumer can determine whether the information in the file is accurate. The National Consumer Law Center and other consumer advocate organizations argue that consumer credit files are replete with errors. U.S. Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) reported that 79% of consumer reports studied contained an error and 29% contained an error serious enough to cause a denial of credit. In addition to information about the CRA, if rules in the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) apply to inquiries relating to RTO transactions (and there are sound arguments that they do not), then the notice must also contain information about why the denial occurred. To the left is an example of a Notice that contains a list of reasons for the turndown, adapted for rent-to-own consumers.

And that is the worst of it, having to send out the Notice.

Dealers often wonder whether they can help customers improve their credit scores by reporting on good payment history with the rent-to-own store. For the longest time, the big three were not interested in RTO payment histories, and they would not include them in a consumer’s file. Nor were they interested in a consumer’s apartment rental or vehicle lease payment histories, for that matter. That attitude is changing as the big three have recognized that there is a world of information out there about everybody that may reflect on credit standing, and that can be collected and sold. In addition, some of the alternate CRAs specialize in certain kinds of information, some of whom focus on collecting information from subprime consumers. Other CRAs collect information about check-writing, medical records and payments, and insurance claims, by way of example. CRAs specializing in subprime include www.microbilt.com, www.ClarityServices.com, www.CoreLogic/Teletrack.com, and www.DataX.com. These and other CRAs would likely be interested in getting rent-to-own customer payment histories.

RTO dealers hardly need another reason to say “no” to would-be customers. That may be reason enough not to bother with credit inquiries of any kind. On the other hand, information about a customer’s bill-paying habits might help a dealer decide how much stuff to rent to someone and when, and how hard to push on the back end of the transaction when renewal payments become late or nonexistent. The credit check world is out there, and dealers may want to investigate it a bit to see if it holds any advantages for their businesses.

Ed Winn III serves as APRO General Counsel. For legal advice, members in good standing can email legal@rtohq.org.

————————————————–

Understanding the Graham Leach Bliley Act

While we are on the topic of consumer financial information, it is worth a few words about the Graham Leach Bliley (GLB) Act. The GLB Act came into law in 2001, in part to protect confidential consumer financial information. It did so by requiring “financial institutions,” as broadly defined in the law, to give consumers notice about what those institutions did with the financial information they collected. Banks and others had developed the practice of regularly exchanging such information with affiliated companies and sometimes selling the information to unrelated third parties, most often to be used by the recipients for marketing purposes. As soon as the law came into effect, questions arose for rental dealers about whether they might qualify as financial institutions, strange as that might seem, and be bound by the law, because certain lessors of personal property were covered.

As soon as the law came into effect, questions arose for rental dealers about whether they might qualify as financial institutions, strange as that might seem, and be bound by the law, because certain lessors of personal property were covered.

GLB and its explanatory regulations defer to the definition of financial institution contained in the Bank Holding Act of 1956. In that law and subsequent regulations adopted by the Federal Reserve Board, certain kinds of leasing activities were deemed closely related nonbanking activities and would therefore qualify the lessor as a “financial institution” under the GLB Act.

However, lessors who “operate, maintain, or repair the [leased] property” are not covered by the Act. Likewise, the regulations go on to explain that only certain lessors qualify as financial institutions for the purposes of the Act, “because leasing personal property on a nonoperating basis where the initial term of the lease is at least 90 days is a financial activity listed in 12 CFR 225.28(b)(3) and referenced in section 4(k)(4)(F) of the Bank Holding Act.”

The brick-and-mortar RTO industry does, as a rule, operate, service, maintain, and repair the stuff it rents to consumers. That language, alone, however, would not let all virtual RTO companies off the hook.

The initial term of most rent-to-own agreements is one week or one month, whether brick-and-mortar or virtual. Occasionally, a rental dealer might put a unit out for a slightly longer term, say two weeks, or even 90 days, but RTO agreements generally do not have an initial term longer than 90 days. This is because rental dealers want the safe harbor afforded by the statutes that define RTO transactions, nor do they want to confuse the marketplace by inadvertently becoming consumer leases under the federal Consumer Leasing Act. Since 2001, dealers have deemed themselves to be outside coverage of the GLB Act. A few state regulators have posed the question to dealers, specifically in Maine and Oklahoma, but once the laws were probed, the regulators went away satisfied that there was no issue for rental dealers. RTO dealers as investors, debtors, credit-card holders, and players in the American stream of commerce get a GLB notice annually from the banks and other financial institutions with whom they deal. It explains what these companies do with the rental dealers’ financial information. The good news since 2001 is that dealers in every state except Maine do not have to send out that notice to their customers.

Maine, uniquely, amended its RTO statute several years ago and added language to the effect that the disclosure provisions of GLB do apply to rent-to-own transactions in the state. In Maine, then, dealers must send out the GLB notice annually. Dealers in the other states have no such obligation, and, but for an occasional letter from state regulators about GLB and RTO, there have been no issues with rental dealers not complying with GLB.

Ed Winn III serves as APRO General Counsel. For legal advice, members in good standing can email legal@rtohq.org.