When APRO’s CEO, Charles Smitherman, called and asked if I would write an article about APRO’s founding for the magazine’s next issue celebrating the association’s 45th anniversary, I readily agreed. I agreed, even though I am off of the payroll and have been comfortably ensconced in easy-going, contented retirement for nine months. My original intent was to craft a piece about APRO’s origins, leaving me largely out of the picture. I find that I have been unable to do so, as my life and APRO’s have been inextricably intertwined since APRO came into being back in 1980.

So, here is how APRO got started with this author playing his dutiful role.

I was, in 1980, a full-time Professor of Business Law at the University of Texas at Austin, tenure tracked. I had determined, however, that after four years in this job, I needed to test my manhood and try out life as a lawyer, at least for a while. In February or so, I gave a legal seminar at a university-sponsored management development event (a bit of moonlighting available to business school professors from time to time). My topic was “The Wonderful World of Government Regulation.” As luck would have it, Bud Holladay was in the room. A few weeks later, I got a letter from Bud inviting me to attend the first ever meeting of rental dealers to be held in Dallas, Texas, the first week of July. He wanted me to give my government relations talk for which he offered to pay a fee and expenses. As I was resigning from UT at the end of the semester to hang out a shingle and become a lawyer, I agreed and went to the meeting.

I had never heard of rent-to-own and did not know who the audience in Dallas would be other than businesspeople in some kind of rental business. I did not tailor my remarks and gave a generic talk about government regulation and business, criticizing regulation and praising free enterprise – red meat for a crowd of entrepreneurs.

There were maybe 30 or 40 people in the room, mostly male, as I recollect, at an airport hotel near Love Field. Bud once told me that the only way to get RTO dealers to a meeting was to hold it at a Holiday Inn with linoleum on the floors close to an airport. He was wrong, and we had marvelous meetings with blockbuster attendance at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas and any number of other exotic locales. Rental dealers like nice places when they have to travel. I have no idea how Holladay made contact with other rental dealers. There were no cell phones or computers in those days. Other speakers talked about financing, employees, customer relations and the like. I stuck around as my plane didn’t leave until the evening. In the afternoon, Holladay opened the meeting up to the attendees. Among other topics, attendees brought up the issue of trade associations. Two reps from GE Capital who were in the room and had given a talk about consumer finance announced that they would have to leave as they could not be involved in conversations about trade associations, and they left. (I knew from anti-trust in law school that a number of GE executives had gone to prison in the 60’s over price fixing done through a trade association.) Someone quipped when the GE guys left, “Gee, maybe we need a lawyer.” I raised my hand, being the only lawyer in the room, and told the group that I was available for whatever they might need as, by then, I was a full-fledged practicing lawyer, albeit with no clients, yet, for all of a month. After all, I was partner in a newly-formed three-man law firm in Austin, had embossed calling cards, and a brand-new lawyer’s attaché case.

Since I was the only lawyer present, the group, led by Holladay, hired me to research trade associations, generally, to see which existing ones might be interested in some type of affiliation or collaboration with this group of RTO dealers and also what creating a standalone association would entail. I was to report back with my findings to the group through Holladay in six weeks.

My original intent was to craft a piece about APRO’s origins, leaving me largely out of the picture. I find that I have been unable to do so, as my life and APRO’s have been inextricably intertwined since APRO came into being back in 1980.

When I got home, the first thing I did was to go to the library and check out a book on trade associations. I learned that there were over 30,000 business and professional trade associations in the U.S. – some giant like the realtors and some tiny like the Texas knitters. (The IRS reported that in 2022 there were over 60,000 registered trade associations in the country.)

I located all of the associations that had rental companies of any variety as members, including the American Rental Association (ARA), the Furniture Rental Dealers Association of America (FRAA), the National Association of Retail Dealers of America (NARDA), the National Retail Federation (NRF), and American Association of Association Executives (ASAE), and others. I talked to all of them.

Some of these groups were interested in aligning with RTO dealers on some basis; some were not. I catalogued my findings, along with preliminary information about creating a stand-alone association, including the rules for a 501(c) (6) non-charitable tax-exempt organization, which is what most business trade associations are. I reported to Holladay and several other dealers and presented my findings. They listened politely to what the existing associations had to say about an alliance, but quickly concluded that they both wanted and needed their own club as the concerns of these RTO dealers, to their minds, were unique and quite different from the issues confronting the members of the other groups.

Next, I dug into how trade associations work, reading scores of bylaws and related governing materials for associations of all sizes. I then drafted bylaws and a code of ethics for the as yet un-named, to-be-created trade association for the benefit of RTO dealers in the U.S. I did ask the group if they wanted to consider an international association, and the answer was no. The U.S. market was plenty big enough for the group, although Sims was of the opinion that RTO would not work in markets smaller than 250,000. While Chuck was right about so many things RTO and was my mentor about the business in those early days, he was woefully wrong about RTO markets.

The real genesis behind organizing RTO dealers came from Holladay and Sims. They seem to have had a number of private conversations about the future of RTO, legal threats, and the need to organize before Bud got busy setting up that first meeting. To a large extent, it seemed that Sims was content to let Bud take the lead in organizing dealers, as Sims was sitting atop a fast-growing chain of large RTO stores, 2000-2500 BOR on average, and trying to keep the wheels on. In a word, Holladay had more time to devote to the project.

Holladay organized another meeting of all the RTO dealers he could find, and I once again presented my findings. There were 30 dealers at that meeting in Dallas, and they unanimously voted to create their own association, as yet nameless. All those present voted to become members. I showed the group my draft bylaws calling for a 16-person board of directors designed to be largely honorary with a six-person executive committee charged with doing the heavy lifting for the association. Before this group adjourned, they elected the initial board of directors, mostly from the dealers in the room, all of whom volunteered for the non-paying job.

That initial board had a number of issues to confront. One of the first issues was the name of the organization. Sims hired his advertising agency to come up with a list of possible names. The goal was to present to the world an association that “put the industry’s best foot forward.” There were, it was generally agreed among board members, some scallywags in the rental business whose practices need to be called out and shunned. There were dealers renting TVs who were persuaded that what they were doing could not be legal and their best plan was to hide under the proverbial rock and hope they didn’t get caught until they could accumulate retirement money. Board members, on the other hand, realized that they had a career in the making – a profitable, long-lasting career with the potential of building companies they could sell for a lot of money – if they could make RTO safe and legal, which was the ultimate reason for having a trade association to begin with.

[They] realized that they had a career in the making – a profitable, long-lasting career with the potential of building companies they could sell for a lot of money – if they could make RTO safe and legal.

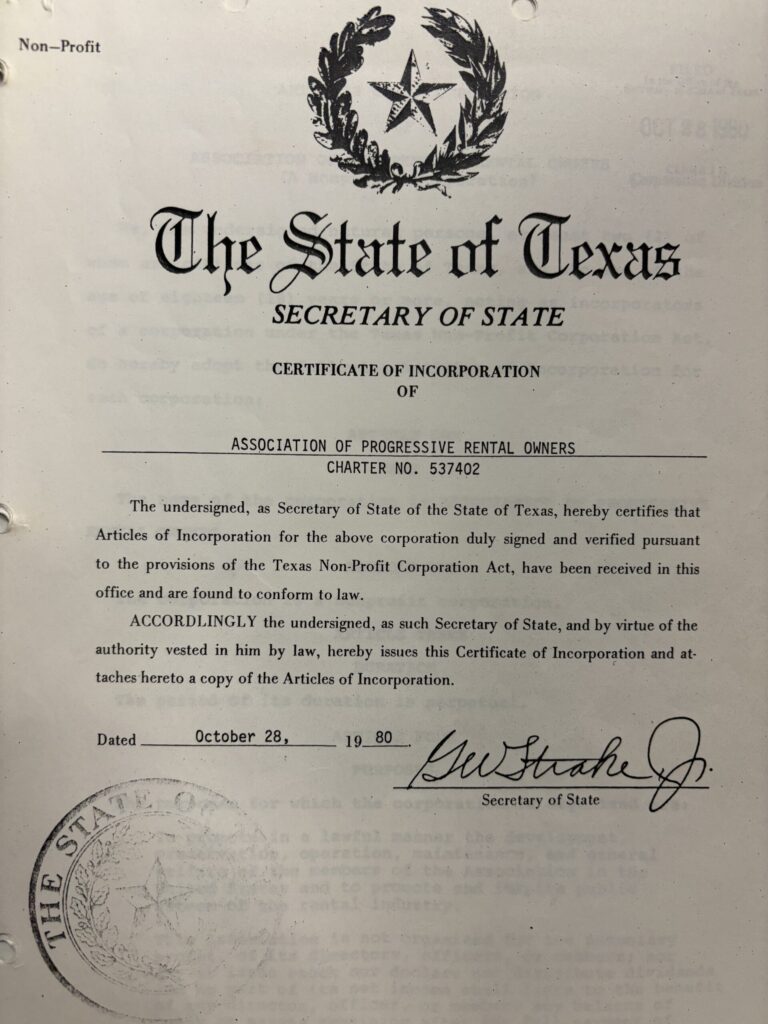

The idea of “professionalism” was much discussed, with the group ultimately settling on the name that still exists today: The Association of Progressive Rental Organizations. I no longer remember how “professional” evolved into “progressive”; only that it did.

Eligibility for membership was a huge issue early on. Some board members were adamant that the association not become a vehicle for helping people get into the rental business. They might be willing to join together to work on industry legal issues, but they were not interested in teaching others how to rent TVs. One dealer whom I was recruiting told me “McDonald’s and Wendy’s don’t sit around talking about how to make hamburgers, and I won’t help other people rent TVs.” Other members favored an open-door policy. “If you want to rent TVs, come on in and learn from the experts how to do it the right way – ethically and legally.” Those members realized that if people were intent on renting TVs as a business, they were likely going to do so with or without APRO’s participation and the danger was very real that bad actors could do real damage to the industry’s image and ultimately the legal standing. The industry had defended 35 or so lawsuits in the 70’s, winning most, but losing a good half dozen, and the attacks were increasing as the industry grew in size. The legal issues raised in those suits were much as they are today – lease versus sale, price gouging, and deceptive trade practices.

The board voted that members, when they applied for membership, would have to have at least 150 units on rent, and do business out of a separate business location, as opposed to a garage and out of the back of a pick-up truck.

The board went through the draft bylaws line by line, accepting 80% of my recommendations and changing the other 20% to suit their better understanding of the business. The board also reviewed and adopted a Code of Ethics to which members were required to adhere, and which was designed to speak to some of the unsavory practices at play in the industry.

There were in addition, a number of administrative issues to be addressed. The board decided that APRO needed to have an office independent of any rental dealer’s facilities. My law firm was subletting 2,000 square feet from another law firm in a high rise building in downtown Austin. We had an empty office reserved for future growth, and I offered it up to the board for a modest rent amount. Then, by default, I became the initial Executive Director, in addition to being the general counsel. It had never been my ambition to run a trade association. I was trying to learn to be a lawyer. However, the association needed staff – board members were all busy renting and collecting – and there is always rent to pay and payroll to meet to new enterprises like my law firm. And, in truth, I was grateful for the gig, and the first year in private practice, I netted a total of $3,000. Holladay was the first President and chairman of the board; Chuck Sims, Jack Callandar, Jim Huff, and Claudia Filloramo rounded out the initial executive committee.

The full board met often enough in those early days, and at full board meetings, there was vigorous debate over the nature of the business, particularly relationships with customers. That necessarily involved what customers were told about the transaction up front. Some board members argued against disclosing the total cost of ownership. If customers are shown that amount, those members argued, they will all walk away from the deal. These dealers asserted that if they had to disclose that amount, they were going to stick it in small print in large paragraphs of boilerplate language, and they did. The other side argued, correctly, as history has shown, that customers are much more interested in the weekly or monthly payment amount than the total cost. And in those days, it was mostly weekly payments – easily 90% of the business. Dealers ran trucks on Fridays and Saturdays picking up cash payments on the doorstep. Card closes and cash on hand were counted late every Saturday night.

A similar issue arose over the “new/ used” disclosure in agreements. Some dealers did not want to make it and argued that customers didn’t care. They just wanted a TV to watch and the chances were great that they would be giving it back after a few weeks anyway. Other dealers argued that at the time of signing in the store, the dealer couldn’t know whether the unit to be delivered was new or used since deliveries were made out of a central warehouse with TVs being plucked more or less randomly off the shelves. Making the disclosure won out of course, although there are still dealers today who want to argue that refurbished can be new.

Dues were, of course, an issue. They still are. The initial board finally settled on dues of $150 per store, acknowledging in advance that some dealers were likely to be less than honest about how many stores they owned. There were then dealers with multiple store fronts who joined with one store so they could observe how the association worked in practice. We still have a few of those dealers.

There was debate over allowing suppliers to join as associate members. Some dealers, notably the ColorTyme franchisor, lobbied vigorously against associate memberships. The franchisor in early 1981 wrote a letter to all franchisees urging them not to join APRO, with the explanation that they didn’t need it. ColorTyme supplied product to its franchisees and got a cut for the service. The concern was that associate members would start selling direct to the franchisees and cut into the franchisor’s revenues. I had a hat-in-hand meeting with Willie Talley and finally got him to tell me he would remain neutral on the association issue as long as the association did not try to start up a buying group. I assured him that the thought had not crossed my mind, and it hadn’t. This issue was an important one for the association’s growth, because there were at the time, some 200 ColorTyme stores in the country. Next came Renco with 50 stores. Trailing below those two were Tom Devlin with 35 stores. Sight and Sound, soon to become Rent-ACenter and Bud Holladay’s ABC Rentals with 15. Most dealers owned one or two stores in 1981.

I read up on what trade associations did for their members. Early on, we tried to collect information from members in order to publish a statistical survey of the RTO industry. Responses were scant the first year and for many years thereafter – not enough responses to make a survey valid. We are still trying 45 years later and are doing a little better these days.

Trade associations put on conventions, and so we did. The first one was in Dallas – airport motel, again, in August of 1981. Admission was free for dealers. We sold maybe a half dozen booths to vendors and lost $35,000 for our efforts. We did get better at conventions and quickly – New Orleans the next year, then Caesars in Las Vegas, then Orlando. People like to go to conventions. Rental dealers are no exception. We put on educational seminars, because that is another thing that associations do for members. The first was Chuck Sims, “Planning: The Process for Control,” in Atlanta. When I got my hands on the seminar schedule, the next one was in Carmel, CA, at a tony inn overlooking the Pacific Ocean crashing on the rocks beneath us. Holladay was just wrong with his penchant for airport motels with linoleum floors, thank goodness.

APRO grew in fits and starts, a lot of the growth coming via word of mouth, dealer to dealer. Most people in the business understood the need for an active trade association devoted to the business they had chosen to be in. A few were too cheap to help pay for it.

APRO grew in fits and starts, a lot of the growth coming via word of mouth, dealer to dealer.

APRO did not spring, like Minerva, full-grown from the head of Jupiter in Roman mythology. Chuck and Bud could not have been sure either what they wanted or what they would get when they organized that first meeting of RTO dealers in 1980. They did know that they were on the front end of a very good business idea with the potential for a huge future. They instinctively wanted a safe and encouraging legal environment for the business which at the time just did not exist. Eventually, as all readers know, through the efforts of scores of devoted and responsible RTO dealers from across the country, APRO was able to “Make America Safe for Rentto- Own.” The struggle for recognition, acceptance, and safety, as with so many struggles, continues.

Ed Winn III was APRO’s first Executive Director and General Counsel.